Pedigree Cats, Inc. Catamaran

Let us

custom

build your dream yacht!

Frequently

Asked Questions- How long does it take to build your dream?

- Can I have what I want ?

- O.K. - I am interested in a Catamaran. What do I do next?

- What to look for when shopping for a Catamaran. "Custom built or Production Catamaran"

- Why foam core? Especially Airex Foam?

- What is displacement?

- What about Range ?

- How much does a custom catamaran cost?

- Why does Pedigree Catamarans, Inc. post our prices online?

- Why do Production Cats depreciate so much more than

custom quality built Cats?

- Why

is it so many catamaran builders that started building a few years

back, no

longer in business?

- CAT OR TRI?

- Can I use a foreign flag vessel in charter service in U.S. waters?

- Insurance?

From Multihull Designers

- What is the minimum size for an ocean-going power catamaran? by Malcolm Tennant

- Displacement vs. Planing Catamarans vs. Displacement Monohulls by Malcolm Tennant

- Power Cats and the LCG by Malcolm Tennant

- Powercat Fuel Consumption Comparisons by Malcolm Tennant

- A Case for Displacement Power Catamarans by Malcolm Tennant

- Large Catamarans by Lock Crowther

- Bridgedeck Clearance for Cats -- Does it matter? by Tony Grainger

How long does it take to build your dream?

Based on our first price estimate, a basic 60' power or sail typically takes about 24 months. This would be a very nice Cat, but not a lot of fancy, expensive items on board (gold faucets etc.) Engines, hydraulic steering, electric heads, windlass, gen.set, etc., very nice, but not a lot of goodies. The second price we show is with almost everything clients really want onboard, Watermaker, A/C, Shore boat, TV (s), fancy wood decor and custom items and electronics. This, of course, also adds more time to construct, maybe 6 months, You can also have us build to a certain stage and you take her home and finish the build or stretch out the time to build to fit your schedule or investments. If you add 6 months to each of these times, it would be for a 75'-85' and 6 months to that and you would be in the 100' range.

Taking her home from here or maybe cruise the San Juan islands, inside passage to Alaska first. Clients have also taken them to Vancouver and had them shipped to Florida or hire a crew to deliever them to where they want.

Yes! 100% But you must stay in the boundaries of the designer structural requirements i.e.. mast placement, weight to be carried and where. All the multihulls we have built over the last 42 years, have been what the clients have wanted, inside and out. Once they find the size they think will work, we find the basic design and designer for their dream platform to create it.

The final look is up to you, either with your drawing or pictures or work with one of several concept artists we know to help. Same with the interior, your interior designer, pictures or cut out from magazine of things you would like or we can line you up with someone to help. You work directly with these people, pay them directly to go as far as you want or need to, the do not work for Pedigree.

Why does Pedigree Catamarans, Inc. post our prices online?

I have been building

multihulls since 1975 and we know how

many hours each boat should take to build, even custom boats since we

do not

build production boats. Other companies

may not have built or built enough boats to determine the cost. Granted boat costs vary directly with the

customer’s requirements, however the hull build should not vary much.

I would be very leery of a company who wants large deposits up front and can't provide basic prices to a customer. What we are hearing now from people that have paid a large deposit up front, only find the builder wants more and more and exceeded their guess of the cost and time line. Then the worst, they want more money or they will sell the cat to someone else, holding it for ransom from the highest bidder, Our clients chose to pay as we build and the cat is 100% theirs from the start and definitely no large deposit up front.

Why do Production Cats depreciate so much more than a quality custom built cat?

Several reasons. One might be, that every cat produced is probably from the same mold and in most cases, several years old and not updated or no improvements incorporated over any previously produced. Thus no real reason to get a new one if you can get the same one used for a lot less. The owners must lower their asking price far enough below the new ones that it will make it desirable. The price on the same new cat, next year, must be in line pricewise, in the marketing field to be sold, thus last years model must be substantially lower

The production cats do not provide the clients with what they expected in a catamaran. Lacking in performance, require a lot of power to move them at a reasonably expected speed, to narrow to give the stability and the room onboard they were led to believe they would have. Deeper draft than expected, very heavy solid fiberglass construction, noisy, sinkable, sweat and hard to maintain a comfortable temperature inside. Most are imported and can not be used for charter in US waters.

One of our custom built multihulls came up for sale, built in 1980 and sold for $60,000 more than it cost the owners to have it built back then.

Even today, we have people trying to buy the clients cat we are constructing from the client and at a substantial amount more than they have into their dream. Problem is, this is their dream and it is not up for sale.

Why

is it so many catamaran builders that started building a few years

back are no

longer in business??

This question

keeps coming up and I think one reason is because most of them wanted

to build

one female catamaran mold and hope everyone wanted what came out of it. Stamp them

out and

try to make their fortune. People now have the tools to research

boats and

builders

and we highly recommend everyone do so. In 1994, about 50

builders

surfaced, claiming to be the biggest and best. I think most are gone

and their web sites no longer come up. Still some inquiries feel

more comfort in the fact that these were to be "Proven Production

cats". Maybe one got built by the "Factory" but most didn't, talk

about the only "One Off" they built. This was the case since 1994 and probably before.

Who designed

some of these offerings in these production Cats. One we know of

was a Monohulls cut in two and widened, with half hulls vertically

mounted panels on the inboard side to plug the hole. Heavy, deep draft,

didn't make it as a monohull and will never make it as a good cat.

Others are from molds made years ago that were for sailing cats.

We are not claiming to be the world greatest, biggest, the leader or any of the sales pitches some use. We do use only proven, name brand materials and proven multihull designers. We do build exactly what the clients want and with very high standards. They are the best and most experienced in their field of designing multihulls, not a monohull designer that would draw anything for a buck. We do insist the clients get their own independent "Marine Surveyor" to monitor the building process as most clients do not have the experience to know if she's being built properly.

Pedigree Catamarans, Inc. has been building catamarans in the Pacific Northwest for over 19 years and Gary Habersetzer has been building multihulls on the West Coast since 1975. “In my thirty nine years of building composite multihulls, I have never built the same one twice, they have all been as different as all my clients.”

The era of production boats is loosing it popularity, one size does not fit all. Today's clients want their yacht to look like they want it to, thus our stylists are available to help there. Custom Yachts give you exactly what you have in mind, inside and out.

Building your dream is a big investment. When carefully done by the right builder using the right materials, the experience can be fun and rewarding.

Be careful, do your research, this is fun and very rewarding if done right. She'll have good resale value as replacement value goes up annually. The biggest thing is that you have what you want, not what a struggling production builder thinks everyone should have and furnished with what he thinks you need. Also be aware, the imported cats also have a smaller market when they are sold, they can not be used in US waters for charter, "The Jones Act" Salesmen never will tell you that, but the info is out there and makes a great difference when it comes time to sell your dream.

CAT OR TRI?

Taken from The Design File, Tony Grainger Yacht Design.

"CATS have become more popular for cruising mainly

because of the accommodation space and privacy they provide and because

for a given length they are faster and cheaper to build than a

trimaran. TRIS, on

the other hand, provide good performance through a wider range of

conditions than catamarans, and can also be effective for cruising by

utilizing flare above the waterline in the main hull, and by fitting

aft cabins where additional privacy is required in the accommodation

layout. Apart from the accommodation, the trimaran provides a more

forgiving motion in a sea way and better resistance to pitching if the

hull shapes are well designed, and the wide beam allows it to carry

more sail in fresh conditions. Against these advantages is the

fact that a cat will require less berthing space and is likely to be

more

maneuverable in close quarters if twin diesels are fitted. Also, the

cat

will have a more steady motion than a tri while sailing

downwind."

I built my first multihull in the 70's and it was a Trimaran,

foam cored, TriStar design, a great multihull. Now I am building

a cat for my wife and I, mainly because of the room, very wide main

salon and stateroom and big aft deck and flybridge. The Tri was

maybe a bit more sea kindly than the cat will be, but besides not

having to build a third hull, she will be a bit faster as well as maybe

a bit more economical.

How much does a custom catamaran cost?

The cost of a custom Pedigree catamaran, constructed with foam core, composite construction is very close to that of a production built yacht. The advantage is, you will have exactly what you want and the disadvantage is, it will take a little while to build.

Charter cats are generally a lot less expensive. They do not need the big ticket luxury items, such as water makers, A/C, big gen. sets, fancy interiors, etc.

When we have an opening to start a new project, you can have just the hulls built and finish the catamaran yourself at a considerable savings at your home port. If you wish, we can provide you with a cat at what ever stage you like. For example, we can fit the engines and aide in completion and when you are ready to launch, we can arrange that as well.

Most of our catamarans are fully loaded and ready for cruising. We have listed the average cost clients have spent on our amenities and pricing page. For a list of some of amenities included in a Pedigree Cat and the average prices, go to our Amenities & Pricing page or click on the "Amenities & Pricing" button available from most pages on our site.

Over the last 20 years, the clients have chosen to pay as we build and they have approved to have done as well as what we purchase for them, engines etc..

All and all, we can provide just about anything you and your

budget can imagine. Our goal is to get you out there to enjoy

the fun with

the exact Catamaran you have always wanted.

I think we are about

the only builder that shows you the price you might spend on you dream,

it's up to you and what you want and need.

O.K. - I am interested in a Catamaran.

What do I do next?

| Step 1 - What type and length do I need?

Common

Questions:

Sail, Motorsailor or Power? Visit the Designer's Showcase and look at a few different yacht profiles and floor plans the designers and concept artists have and they have more. We can help you find a cat that, size wise, to start with based on the answers to the questions listed above, plus we have others not shown. Keep in mind the floor plans and nonstructural changes can be modified before construction begins to ensure that this is the yacht you have in mind. There are a lot more than what is shown there, but these will get you started and keep in mind, these were drawn for someone else and are not set in stone. Ultimately, you will need to determine the approximate length, and select the profile and floor plan to start working toward what you have in mind and fit your budget. Our stylist can also help put your dreams on paper. The designers links on our site has other models, plus, they are pretty much available to design you your own cat. There are also links for the Concept artists that have a few ideas shown on our site. You are pretty much unlimited as to what your dream can

look like, inside and out, it is up to you, we are not a production

builder that thinks you should have what they like and produce (the

same every year) We have never built the same thing twice,

they have all been as different as our clients and their dreams. Dick Newick, multihull designer for forty years is famous for saying "You can have two of three factors in a multihull - speed, comfort, and economy. You cannot have all three." That is true, but could depend on how fast you expect to go. While true for sailing cats, the new displacement power

cats

are able to do quite well, reaching speeds of 20 knots with very little

horsepower. Cats must also be balanced and not over loaded, to

perform as

the designer has projected. Extra weight to be carried must be

disclosed to the designer before adding and before building. |

| Step 2 - What is included and how much is it

going to cost?

Visit our Amenities and Pricing

page to get a list of some of the items included on a Cruise Ready,

Pedigree

Cat. You can sail away knowing you have all the necessary safety gear

and

amenities onboard. These are updated after every cat is build or being

built and prices have changed on the products purchased. We have been able to determine an average Pricing

Guideline

for your information. These are an average price for a Pedigree

Cat

power or sail, with all the amenities listed as an ocean ready

yacht.

Of course, pricing may change depending on if you want, gold plated

faucets or require additional equipment onboard. Also, charter

yachts are generally

less than the price listed, while trimarans generally cost more than

the

price listed. The larger sailing cats do not show the cost of the

rigging as it varies so much with what the clients may want i.e. roller

furling systems and electric or hyd. winches. |

| Step 3 - Contact Us

There are many more designs available than are shown on

our

site. Most designers have design catalogs and study plans

available

at

very reasonable prices. If you need more help in locating exactly

what

you have in mind, we are able to have it designed. You may also

use

the stylists on our web site (links) our stylist to lift the sketches off the napkins and bring them to

life. Call us anytime,

even week ends, we are generally here showing clients one of the cats

that are here under construction. For More Information, email us at Info@PedigreeCats.Com Please provide us with as much information as possible

so

that we can better assist you. We really hope you get to have your dream, it's an

experience I wish everyone could have, we did and can't wait for the

new one, so we can get back on the water |

Why foam core?

Foam core has several advantages: no deterioration, insulated, virtually unsinkable and stronger than solid fiberglass and Aluminum when tested in the same manner.

Foam

core

sandwich construction is the most technologically advanced form

used in construction today, especially in conjunction with E-glass,

Kevlar,

Carbon Fiber and Structural foams. Structural foams are

classified as load carrying, closed

cell plastic foams that are non friable (will not readily crumble when

stressed). Each designer calls for the materials to be used in

the building process, including foam,

fabric and resin. Pedigree Catamarans specializes in

foam core construction only. The foam used in the hulls,

bridgedeck and bulkheads of our catamarans is generally Airex®

R63 because of its high impact specifications. This foam is a

resilient, thermoformable linear linked, PVC foam core material with

exceptional slamming load dissipation characteristics. Divinycell H

foam, a Polymer foam is used

above the

bridgedeck. Other

specified foams may be used as the designer specifies.

Clients have realized that their multihull has gone up in

value

over the years, because of the foam core material and because of the

replacement cost. Airex® foam core and sandwich construction

produces a catamaran that is 35 times stronger than solid fiberglass,

wood or aluminum according to Airex manufactures. It

is also is about 30 percent lighter; will not rot or corrode; does not sweat and

provides floatation that makes the catamaran virtually unsinkable (yes,

everything can sink if put enough weight on it.)

What is displacement?

Displacement is how much the boat weighs and is the weight of sea water she will displace when floating. Foam core construction is about 30% lighter than solid fiberglass, Aluminum according to foam core manufactures. When the designers use the term "full displacement", it usually means the vessel is cruise-ready with equipment and fuel or with the "useful load" on board. While "light displacement" means empty and where it doesn't even have fuel on board. Lighter construction allows more payload to be carried and smaller engines to reach a good cruise speed, which uses less fuel, allows greater speeds, shallow draft, etc..

This is something to look at when you start comparing cats, there

weight. Our 50' cats weight in at an average of 15,000 lbs. empty and

draw about 30" (rudder and props are the deepest.) Where most

production cats are up closer to 50,000 lbs., deeper draft, more HP to

get them up to an acceptable speed, must carry more fuel to get her up

there as well as the bigger engines. The designers we use have

displacement hulls, about 18 to 21 knot range of speed with reasonable

HP and fuel consumption.

What about Range?

A little about under power....as under sail with a little wind, you are unlimited. The engine manuals usually have a chart, but a common method to get an idea of range is to divide 20 into the horsepower of each engine. This will give you an idea of GPH you would burn at the higher continuous RPM per engine. I have found that for each cylinder at idle burns about 1 quart of fuel...so 6 cylinders is about 1.5 GPH at just above idle or 1,000 RPM achieving hull speed on a calm day.

A cat on a calm day can reach hull speed with one engine at just above idle. Hull speed in knots is figured by taking 1.34 multiplied by square root of the water line length of your cat. Lets use about 10 knots or 11-12 mph and that will give you some idea. I like to put enough fuel onboard to have about a 1,000 mile range at cruise speed (rpm) say somewhere about 15 mph and this usually takes both engines to do that, but not wide open. From California to Hawaii (non-stop) close to hull speed, that is where you have the best range and least resistance, even better, motor sailing. That range will also get you to the next fuel dock or allow you to pass up the island that just got their fuel they have waited 6 months for and will cost you a lot to take it away from them.

The designers place the fuel and other liquids in the hulls where they do not affect the trim, under the sole or hull floors and lots of room down low. In most the cats we build now, the tanks are very large and built into the hulls, epoxy coated with baffles about every 50 gallons. A 75' to 86' has 1,000 galons per side, again, you don't need to carry around fuel, but if you find an island or another boater in need, trade it.

From Malcolm Tennant:

Superior Performance

of

the Displacement Power Catamaran

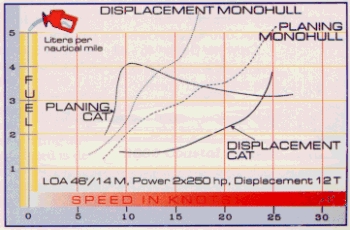

The bottom line on the graph is what you are after, its hard to read,

DC

displacement cat.

Fig.1. graphically illustrates the superior performance of the

displacement power catamaran. No other configuration gives you

the combination of

comfort, relatively high speed [very high speed in comparison with a

displacement

monohull] and long range cruising. The smaller designs; below 16m, can

in

some cases go Transocean but only at relatively slow speeds because

they

do not have the capacity to carry enough fuel for longer trips at

higher

speeds. The larger vessels, from 16m up, can go Transocean at speeds

from

15 to 20 knots for two to three thousand miles on their basic inbuilt

tankage.

This is the sort of performance that had previously only been available

in

monohull in the 40m+ range. The very low fuel usage that is evidenced

in

the graph means much lower operating costs. This, combined with the

very

good seakeeping, and the unprecedented stability which is inherent in

the

displacement catamaran, introduced a new concept in long range travel

at

sea. And of course the smaller horsepower requirements for a particular

performance

reduces your initial capital cost also.

Bridgedeck Clearance for Cats -- Does it matter?

This exert has been taken out of Tony Grainger's design

catalogue. "The answer might seem obvious to anyone who has

sailed bridgedeck cats offshore,

but it isn't so obvious to the newcomer to multihulls and one could be

excused

for asking the question when we see the proliferation of

production

cruising cats with relatively, and sometimes very low bridge

clearance.

Excessive clearance will create undesirable windage and it also

increases the gap between the boom and the water, which is a major

factor in reducing the efficiency of the rig from induced drag.

However, it must be remembered

that abridge clearance is reduced as heeling takes place and if the

clearance

is inadequate, safety, comfort, and overall performance will be

compromised.

So what does it matter? Wave slamming is most likely to occur

upwind

when the pitching of the boat interacts with the occasional steeper

wave

to cause slamming under the bridge. However, slamming can occur

on

any angle of sail including downwind and is typically experienced on

Australia's

East Coast when there is a residual short sharp swell left over from a

fresh

northeasterly, combined with the more even south easterly swell which

is

almost always present, even if only small.

The effects can vary from the occasional distraction of a dull thump

under

the bridge, to constant impacts which will slow the boat, and severely

impede

progress to windward, and in the extreme will lead to structural

damage.

So how much clearance is enough? It depends on the width of the

boat

(a wider bridge has greater exposed flat area), the degree to which the

boat

pitches, (subject to hull shapes), and to what extent you value

performance

(and by implication, safety) as opposed to retaining a low profile

However,

it could be said that a clearance of much less than 6% or 7% of LOA

would

be generally considered to be low for an offshore sailing

catamaran.

Power Cats and the LCG

From Malcolm Tennant, Professional Boat Builder, April/May 2000

An overweight multihull with trim problems is not easy to fix. Some keelboat designers and builders take a rather cavalier approach toward mass and longitudinal center of gravity (LCG) calculations. In many ways this is quite understandable. By adding and subtracting ballast, the displacement of most monohulls can be adjusted relatively easily after the vessel is built. (This excludes high-tech boats, such as America's Cup competitors, which have ballast ratios of around 80% and ballast concentrated in the keel bulb.) The LCG position can be changed by moving the ballast fore-and-aft to affect trim; the keel can be repositioned; and the mast can often be moved-admittedly all a bit drastic and undesirable. But post-hoc solutions to a trim, or an overweight problem, are possible. In fact, these things may often be done so the vessel will achieve a more favorable rating for racing.

Multi-hull-sailboat designers, on the other hand, don't have any of these luxuries. They may be able to move some fluid tanks around a bit, but this is only a partial solution, since the tanks change weight as they consume the fluid and they constantly need to be topped off to maintain trim. There is no ballast; there is no keel; and the mast stays right where it is, unless you're willing to tear out the structure the mast rests in and rebuild a major part of the internal framework. To compound this problem, the difference between the light-ship condition and the full load displacement can be as high as 30% or more; so mass calculations that are not precise can result in a major trim problem.

An overweight vessel also affects the safety factors calculated into the rig and structure. Loads on rig and structure are calculated for the full-load situation, and with a particular safety factor appropriate to the vessel's intended use. If the vessel is heavier than the designed full-load displacement, then things such as the righting moment and transverse bending moments are higher, which erodes the safety factors in the structural calculations. Unless the overload situation is extreme, it's unlikely it will lead to immediate rig or structural failure. But it will almost certainly mean that the rig will need replacing earlier than would otherwise have been the case, and some structural problems, such as cracking, may occur with age.

Power-monohull designers are in a similar situation. They don't really want to add ballast to correct a trim problem if they can help it; this could exacerbate an existing weight problem.

Power-multihull designers, however, must treat the mass estimates and the calculation of the LCG position as the proverbial Holy Grail. If the vessel is a planing power cat, then the mass estimate and the LCG position are critical. The planing catamaran tends to have a smaller planing surface and higher bottom-loading than the equivalent monohull. Because it almost certainly has more skin area, it also tends to weigh more than the monohull, unless it's built out of advanced composites. If it's overweight and the LCG is in the wrong position, affecting the trim, then there's going to be a major problem getting it to plane. It may, in fact, end up as a rather inefficient displacement boat. [There are also critical factors in dynamic instability. For more on this, see PBB No.31, page 20-Ed.]

You may think that because weight, per se, is not the same problem from a performance point of view for a displacement catamaran, the mass and LCG calculations would not seem so critical. Wrong! The displacement cat usually has finer hulls than a planing cat (and much finer than a monohull), which gives it a higher hull speed. This makes it more susceptible to changes in longitudinal trim because of the narrower waterplane. It's basically the difference between a plank floating on its edge or on its flat. If weight is added to the end of the plank floating edgewise, then it will "dip" a lot more than the plank floating on its flat with the same added weight. So the position of the LCG relative to the longitudinal center of buoyancy (LCB) and the longitudinal center of flotation (LCF) is crucial, since relatively small shifts in the position of the LCG can cause serious trim problems. What this means in practice is that it's very difficult to keep a power cat in level trim in all conditions from light-ship, through half-load, to full-load displacement; this is especially true of the displacement cat. On vessels with a substantial difference between the light-ship and full-load conditions (such as those craft with transoceanic or long-range capabilities), it's common to arrange a fuel-transfer system to keep the craft in trim as the fuel and water loads change. More seriously, it also means that any increase in weight or shift in the designed LCG position during construction can be disastrous.

An increase in weight may have very little influence on the performance of a displacement power cat (one of our ferry designs, for example, performs with 150 people much the same as when it's empty). This is because the major determiners of hull speed, such as the prismatic coefficient and the ratio between the waterline-length and waterline-beam, are little affected by any immersion.

If the extra weight affects the trim, however, then it adversely affects the performance. Stern-down trim can often reduce speed by a knot or two, but more important, the weight increase may also compromise the performance of the vessel by lowering the height of the wingdeck off the water, causing the waves to hit the wing in milder conditions than might have been the case if the vessel were at its correct displacement. And, in similar fashion to the sailing catamaran, the structural integrity is compromised because the loading on the structure are higher than those in the original structural calculations. This lower wingdeck height severely disturbs passenger comfort, their peace of mind notwithstanding, since waves thump more frequently on the wingdeck.

Weight also increases the longitudinal rotational moments of inertia of the craft, particularly if the added weight has been distributed toward the ends of the vessel. The bows are slower to rise to wave action, which further increases the likelihood of wave impact on the wing, particularly at the leading edge. When the bows come back down again, the wingdeck will hit the water harder, Even in normal conditions, weight should be concentrated toward the center of the vessel as much as possible to minimize the pitching effects that are more evident on the slim-waterplane catamaran.

To counter wingdeck impact, some designers place a vestigial third hull in the center of the wing, up forward - similar to the center "hull" on a wavepiercing catamaran, though somewhat smaller. This obviously costs more to construct than the flat wing, but may be a way of minimizing the impact of the additional weight that always seems to sneak in. It doesn't do any harm to have extra length of empty boat at the ends and to keep the wingdeck as short as possible, and as far back from the bow as practicable. If I can, I prefer to bring the wingdeck up to gunwale level some distance back from the bow; the area forward of this is then left open. A "pickle-fork" bow, with perhaps a trampoline or a forward deck from gunwale at sheer height, is fitted. This forward deck is well off the water (right up at gunwale height) and the central anti-slamming nacelle is brought forward under this area. I carry the nacelle right aft thought the underside of the wingdeck where it becomes a very convenient duct for pipes, holding tanks, etc. On my more recent rough-water performance designs, I have used a "double arch", which has a cross section similar to (but smaller than) those employed on some early wave-piercing catamarans. All these approaches minimize slamming should it occur. Keeping level trim with the wing at the designed height, however, is the real name of the game.

It has also been suggested that the "unknown-items factor" should be increased to compensate for any possible added weight. This "fudge" factor allows for the weight of those small things that are difficult to estimate, such as bolts, screws, clips, hinges, and the like. If this factor is assessed with any precision it will increase the design cost considerably because of the amount of time involved. The unknown-items factor is usually expressed as a percentage of the structural weight, or light-ship displacement.

To some extent an increase in the unknown-items factor can be justified as compensation, but there are a few problems associated with this approach. First, it degrades the accuracy of the whole weight-estimating process and makes it more and more of a guess. If the factor is too big, then there isn't much of a reason to even estimate the weight; you may as well just stay with the original "best guess" established at the beginning of the design process, which is based on previous experience. If you don't have a lot of experience, then you would just have to accept all the uncertainty that goes with it, particularly if you haven't designed a similar vessel before. The basic assumption about all the small items that make up the factor is that they're evenly distributed around the structure of the vessel and, therefore, do not affect the LCG position, only the weight . But. if major items are added to or moved around the vessel after the weight estimates are completed, then they can have a marked effect on the LCG position.

Power-multihull designers must make sure that the mass and LCG calculations are as precise and comprehensive as possible, Impress upon clients, in the strongest possible terms, that they must tell you everything they're going to have on the boat, even if they're not going to fit it at the moment. ( I have a checklist these days to help with this.) A client can't keep adding equipment to the boat after the design stage is finished. This is a major problem with catamarans of all types because of the amount of interior volume that's generally available, Unfortunately, because of the large load-carrying capability, the owners must be restrained from filling up every available space, particularly with heavy items.

Assuming that the owner can be kept under control, then there's the question of possible differences between the builder and the designer. How do you ensure that the builder is working to the same weights as the designer? This isn't too much of a problem with alloy [aluminum] construction. Because the plating is produced under tightly controlled conditions, you can rely on its being a particular weight per square meter within very close tolerances, and this makes the mass estimates relatively easy, aside from the question of filler. But, in the case of a composite craft, whether it's wood, foam, fiberglass, balsa, or various combinations of these, the construction material isn't manufactured in a factory - it's made on site. Designers use particular fiber-to-resin ratios, thicknesses of plywood, weights of fiberglass, etc., for their mass estimates. These should be based on actual achievable, as-built-in-a-yard weights, not laboratory perfection. But if the builder is not achieving the same weights per square meter as the designer intends - or the builder changes the material - then things can get seriously out of whack very quickly. The solutions to this problem are twofold. One, the designer can get actual, as-built weights from the builder. Unfortunately, this only works with the second boat from a particular builder, and doesn't necessarily work for all of them since laminate-weight variations can be as high as 25% from builder to builder; even with individual laminators at a given shop applying open-mold, hand-layup techniques. Second, some builders institute careful quality-control procedures covering the laminating techniques and the fiber-to-resin ratios to ensure that they're getting the correct weight estimates. SCRIMP (Seemann Composites Resin Infusion Molding Process), pre-preg fabrics, and wet-out machines may offer better control over fiber-to-resin ratios, at least for a primary structure.

Communication between the designer and builder concerning the actual weights is crucial and this is no less true for a wood/epoxy composite boat. [See the sidebar on page 49.] To this end, it's advantageous for the designer to supervise construction and be aware of any problems as soon as they become evident. In fact, designers who supervise construction should be constantly on the lookout for any deviation from the plan that's going to have a deleterious effect on the mass of the vessel. The builder can also construct the boat on load cells, or at least weigh the vessel at particular intervals, allowing the builder and designer to monitor the vessel weight and the LCG position as construction progresses. At a particular stage of assembly, if weight is high and the LCG is not where it should be, then it may be possible to take corrective measures. If all weighing happens at the end of construction, then it may be far too late and the unhappy owner is left with a boat that doesn't perform as expected, and with a set of problems that will be expensive to remedy.

A Cautionary Tale

My assistant and I performed nearly three weeks of calculations on a

comprehensive

spreadsheet to get the mass and LCG estimates as precise as possible on

a

19.6m (64.3') power catamaran designed for

strip-plank/ply/foam/fiberglass composite construction. In fact, it was

probably the most careful mass estimate

we had ever done.

When the vessel was launched, it appeared to be floating over its lines. We took measurements from the waterline, and the computer confirmed that in light-ship condition the boat was 27% heavier than the weight estimates. So what had gone wrong?

I had only visited the vessel once in the early stages of its construction because it was being built at a considerable distance from my home base. Somebody told the owners that extra weight did not have an adverse effect on displacement power catamarans. That was correct with regard to speed, but they seemed to be totally unaware of the negative effects on vessel trim-despite my earlier emphasis on weight when discussing the design with them.

So where had all this extra weight come from? Unbeknownst to us, the builder had substituted 150kg/m3 (9.37 lb/ft3) end-grain balsa for the specified 60kg/m3 (3.75lb/ft3) PVC foam in the core of the ply/foam/ply structures of the wingdeck, bulkheads, and cabin top. The area involved was several hundred square meters. The exterior sheathing glass was 750g/m2 (22 oz/yd2) instead of the specified 300g/m2 (8 oz/yd2). Factoring in the resin, this is a significant increase in weight. The plywood specified for the interior cabinetry was 4 mm to 5 mm (.16" to .2"); actual ply in a lot of places was 12 mm (.5"). Was the builder the source of the problem? He certainly contributed, and commented that none of the increases in weight was very much. But if you say that 200 times, the result represents a significant increase.

The owners also had the builder move the rather large galley some 2m (6,6') forward and they installed commercial/hotel appliances rather than the domestic units we had allowed for. To compensate for the resulting bow-down trim, the builder put 500kgs (1,100 lbs) of batteries aft. This may have corrected the bow-down trim, but it magnified the longitudinal moment of inertia already initiated by the forward galley.

What could we have done? The owners weren't willing to pay for

supervision, but we should have insisted on being informed -in writing-

of any design changes.

We should also have insisted that the vessel be built on load cells, or

at

least weighed several times. If these things had taken place we might

have

been able to notice the problem earlier. Isn't hindsight wonderful?

What is the minimum size for an ocean-going power catamaran?

Taken from The Power of Multihulls, Spring 2000, by Malcolm Tennant:

"I am often asked "how small" a power catamaran can be and still be used for serious ocean going. This is really a "how long is a piece of string" type of question, but the St. John 44 is a serious attempt to actually answer it.

The biggest problem when talking about the size of any catamaran is that people tend to confuse size with length. In the case of a monohull vessel, a longer boat is usually a bigger boat. In the case of the catamaran this is not necessarily so. You can have catamaran with, say, 18m hulls but with the superstructure of a 12m boat. This will be perceived by most people as being a big boat, when in fact, it is just a long boat that is still quite small in volume. It is also perceived that this longer boat will also be a much more expensive boat. But, again, this is not necessarily so. Given that the cost of the hulls of a catamaran is somewhere in the order of 10% of the total cost of the vessel, making the hulls a couple of meters longer has very little effect on the cost of the vessel. It may actually decrease the capital cost, as the boat may now be able to attain the same speed with smaller [cheaper] engines.

However, given that the general perception is that a long boat is a big boat and, of course, the usual marina berth problem, I have tried to restrict the overall length of the St. John 44 to what I consider is a workable minimum for an ocean-capable power cat. The effects of this restriction are twofold. Because people still want to carry pretty much the same equipment on the shorter boat that they would on the longer one, and are still looking for the same sort of range, we have had to use a wider hull than is our norm to get the necessary load carrying capability. This then has the effect of lowering the vessel's hull speed and reducing its efficiency slightly because we are now operating farther up the hulls resistance curve. But, we will still get around 25 knots out of 230 hp per side - perfectly satisfactory performance for a vessel of this type. Even if it is a little less than we could normally expect to get from one of our boats of this displacement.

We often have all the cabins on the wing deck with walk-in access. However, this usually means that, if an enclosed wheelhouse is then placed on top of the main structure, and a good wing deck clearance is maintained, the overall height of the boat is substantial. In this design this was not an issue. The clients requirement of having an internal helm on the main deck meant that visibility out the front of the boat was a necessity. Consequently, the forward berths have sitting headroom only, so the helmsman can see forward over the top of them, and are placed in the wing with access from the hulls. This is the configuration that is common with most sailing catamarans. The owner's stateroom, however, is located on the wing deck with an en suite head and shower. The saloon, galley and dining areas are all located on the same wing deck level and use household appliances where possible. The stern cockpit features an aft-facing seat (great for fishing) and generous boarding platforms to port and starboard. The flybridge has a second helm, a davit and stowage for a rigid bottom inflatable dinghy.

We have used our standard hull form that has become the shape of choice for most designers of displacement power catamarans since we first evolved it some fifteen years ago. This includes totally protected propellers, installed on a perfectly horizontal shaft in such a way as to completely eliminate the appendage drag normally associated with shafts and struts.

Our usual hull beam, and buoyancy, increasing knuckle is there along with the underwing girder on the inboard hull side and the central wave breaking nacelle. All features that make our designs particularly good rough-water boats.

Propulsion is by normal four-bladed propeller with the tail shaft attached to a thrust bearing so the boat is being pushed on a bulkhead rather than on the engine. The engine is connected to the thrust bearing by an intermediate shaft and can therefore be more softly mounted, considerably reducing noise and vibration.

We have managed to get most of what the client wanted into this design and we have still retained our generous wing-deck clearance and all the other features that, in our experience, make for a good offshore boat. The vessel also has a range of 2,500 nautical miles at 12 knots.

So, I would have to say that, in my opinion, the St. John 44 is about the minimum size for an ocean-going power catamaran." (This by Malcolm Tennant)

Can I use a foreign flag vessel in charter service in U.S. waters?

The following discussion is intended to provide general guidance as to issues that may arise for a particular transaction. Such issues are best considered on an individual case basis.

Any foreign vessel entering for navigation between ports in

U.S.

waters must be imported, requiring payment of an import duty,

or must obtain a U.S. Customs cruising permit. The cruising permit

does not allow commercial activity while in the U.S., such as

charter service.

A foreign flag vessel, which has been imported, is restricted

from

carrying passengers from one U.S. port to another, or from carrying

passengers within U.S. waters without a foreign voyage, because

it is not eligible for a coastwise trade license. 46 U S.C. 12106.

Only U.S. documented vessels are eligible, and vessels which have

been foreign built or foreign owned are excluded from this license.

46 U.S.C. 12106(a)(2); 46 C.F.R. 67.17-5(c). Congressional exemptions

may be granted to

these requirements, on a case by case basis.

A foreign flag vessel which engages only in foreign voyages,

including cruises to nowhere into international waters, would

not be in violation of Coast Guard restrictions, though it would

have to clear U.S. Customs for each entry and exit. If it is operating

as a vessel carrying passengers for hire, there will be inspection

requirements which verily compliance with foreign flag state

requirements

and compliance with U.S. laws.

A foreign flag vessel which has been imported into the U.S. and

engages in bare boat charters in U.S. waters must comply with

the State requirements for registration and sales tax, and must

still clear on every exit and entry from a U.S. port since it

is a foreign vessel without a cruising permit.

Based on what experts say, they advise boaters to stop worrying about their insurance and start thinking about how to afford their next boat. Unless you have an arm-length history of claims or are planning to set sail for Tahiti in a ’68 rust bucket with only your significant other as crew, buying insurance shouldn’t be high on your list of worries.

"It's not about the boat, but the individual. It has to do with individual risk. Obtaining insurance depends on the past experience of the boat owner."

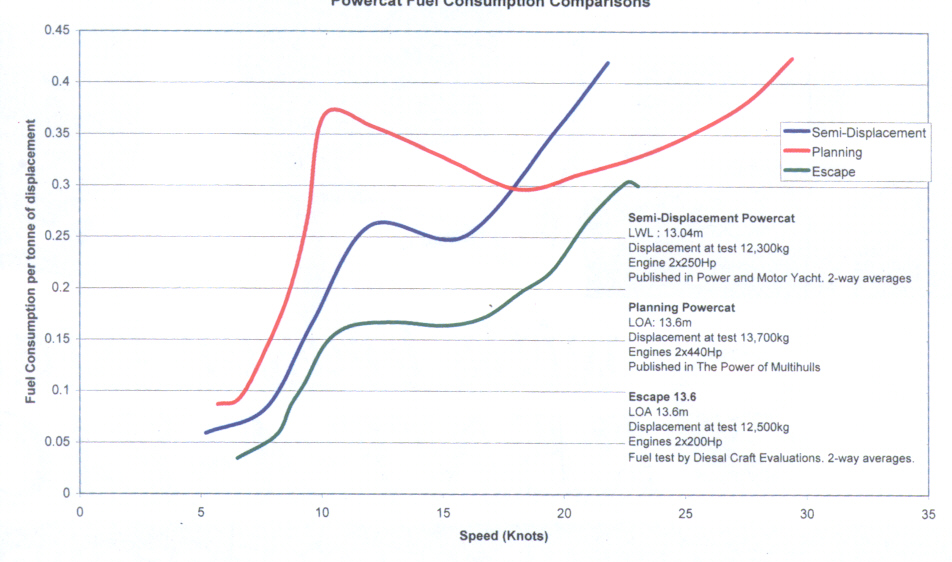

Powercat Fuel Consumption Comparisons

by Malcolm Tennant Multihull Design LTD

by Malcolm Tennant

Frequently in magazines and on web sites you will find claims of 'greater speeds', 'lower fuel consumption', 'longer range' for a particular design. Here at Malcolm Tennant Design Ltd, we pride ourselves at producing fuel efficient powerboats which give high speeds on displacement hulls with as low as possible horsepower requirements. Our efficient hulls allow for longer ranges with a given amount of fuel. To make sure we are delivering the best possible performance to our customers, when possible, we like to compare our hull performance data with other boats as a validation of our design ethos. When fuel consumption tests are published, it allows everybody to look beyond the advertising blurb and estimated performance figures and get down to what a boat is really achieving.We recently had the 13.6m Escape launched here in New Zealand and had a fuel test completed on her. We managed to find two other published fuel tests for recently launched (2003) vessels of comparable designs. These other two boats have been designed by reputable designers that are competent in designing power multihulls.

The other results are for a round bottomed with chine semi-displacement powercat and a hard chine planing powercat. The fuel consumption was matched to the displacements of the vessels so that the slightly heavier planing cat would not be penalized. Our vessel, the Escape, is a full displacement hull that is Malcolm Tennant's signature powerboat hull form.

The results are shown in the following graph. Right across the fuel range the Escape was using less fuel than either of her competitors. Her closest rival below 19 knots was the semi-displacement powercat. However, as can be seen from the graph above 10 knots, the Escape is using on average only 65% of the fuel of the semi-displacement vessel! Even below 10 knots the Escape is only burning 60% of the semi's fuel. This means more than 40% more range for the Escape at a given speed.

At all speeds compared, the planing cat was using more fuel than the Escape. At the planing cat's drag hump at around 11 knots the Escape was using only 43% of the horsepower of the other boat! Above this speed the other boat gets onto the plane and her fuel consumption begins to drop until 18 knots where it begins to rise once more. At the top speed the Escape reached with her 200 Hp motors of 23 knots she is burning only 90% of the fuel of the planing cat. The planing cat then uses an additional 480 HP (total) for another 6.5 knots of speed! So unless very high speeds are required in a boat of this length, the displacement cat is superior.This figure also shows the second advantage of the displacement cat in that the speed can be reduced to a slower cruise speed for a greatly increased range. If we look at 15 knots for example, the Escape is only using 50% of the fuel of the planing vessel. For a given amount of fuel this equates to twice the range! To increase her range, the planing cat could increase her speed to 18 knots. At this point she would still only have 55% the range of the Escape. The other option for the planing cat would be to reduce her speed to 8 knots to achieve the same range as the Escape achieves at 15 knots. At 15 knots the Escape has a range of 616 nm (with 10 % reserve) and she would cover this distance in 41 hours. The planing cat would take 77 hours to complete this trip. This means she would arrive 1.5 days later! On a return trip cruise you would lose three days out of your holiday just to passage making!

This has confirmed

for us that our displacement powercat hull form is the ideal cruising

power boat, capable of both high top speeds and extended cruising

ranges that cannot be matched by the other conventional hull forms

compared here. To the owner, this equates to lower fuel cost and

more time spent on holiday and less time passage making, which should

keep everybody happy!

A Case for Displacement Power Catamarans

Article by

Malcolm Tennant as published in Multihulls Magazine

In our Premier Issue, Malcolm Tennant, one of today’s foremost power catamaran designers, discusses the principles of planing vs. displacement catamarans. In this article he makes clear his choice of the displacement cat.

For some fifteen years now our office has been designing powerboats that combine something of the old and something of the very new. To make a leap forward in comfort and economy we looked back to the close of the 19th Century and the early years of the 20th. We have taken the powerboat wisdom of that time and used it in the designing of very modern power catamarans that can have much more living space than their monohull cousins, and that easily surpass them in comfort and economy. Current thinking has it that to go fast in smaller craft it is necessary to plane. This is because the usual monohull displacement craft are restricted to a speed of approximately 1.34 times the square root of their waterline length (Froudes Law). To drive a normal displacement vessel faster than this requires an inordinate amount of horsepower and may even lead to foundering in their own bow and stern waves, or by rolling the gunwales under from the enormous torque produced. Planing is a way to circumventing Froudes Law by getting the vessel to plane on top of the water where the wave making drag is no longer a restriction on their performance. However, planing craft do need to be relatively light, i.e.: have good power-to-weight ratios, and planing surface-area-to-weight ratios; are very inefficient when they are not planing, and are not as economical to run at some speeds as the displacement craft. So we seem to have two distinct type of boats: a. One that is fast, but uneconomical at slower speeds and can have a bone-jarring ride in a seaway; b. The other, that is economical and comfortable in a seaway, but is slow. Is it then even possible to get a craft that combines the best features of both these types? A boat that has reasonable, even good performance with excellent accommodations and is still economical to build and run and has good seakeeping capabilities: or is this just one of those designers’ pipe dreams?

One quite successful attempt to achieve this dream was made by Tom Fexas with his Midnight Lace series of monohull designs, in which he used long, light, semi-displacement hulls to improve economy without compromising performance too much. These boats were, in fact, a compromise (aren’t all boats?) and, to me, only partially successful by reason of his definition of a slim hull which was, of course, forced on him by the need for stability, accommodation and sea keeping. To Tom Fexas a slim hull was one that had a length-to-beam ratio of four (the waterline length was four times the waterline beam). This was certainly narrow by contemporary planing boat standards, but was unexceptional when compared with earlier boats, or with types of hulls that I am proposing should be used.

Before the improvement of the power-to-weight ratio of the internal combustion engine, and the development of the hard-chine, low-deadrise hull that allowed boats to plane, there was only one way to go fast: building long-and-slim, and in the first decade of the 20th Century we find boats such as Slim Jim, that were achieving speeds of 15 knots from a 15 HP engine driving just such long hulls in 1905. Typical of the early boats was Defender: 16.2m (53') long, having a maximum hull beam of 2.28m (7'6"). Headroom under the flush deck was only 1.45m (4'9") and she slept six in berths only 500 mm (18") wide. In anything of a seaway it would have been incredibly wet and uncomfortable. The boat had a great deal of grace and elegance to her lines, but her rolling at sea, and lack of accommodations, would be totally unacceptable today except for one small detail: a 48 HP motor propelled this 16.2m boat at 16.5 knots! Is it possible, then, to reconcile these old, easily driven, but incredibly uncomfortable hull forms with the current, ever increasing demands for more interior space and more home comforts that can be the downfall of many a well-designed planing craft? I believe the answer is: catamarans! By joining two of these long, slim hulls together and surmounting them with an extensive superstructure, we are able to provide even more than the currently desirable amount of accommodation and at the same time stabilize the hulls so that rolling is no longer a problem.

Even a very cursory look at sailing catamarans will show that they are not restricted by Froudes Law. Their very fine hulls place them on a very different part of Froudes’ wave making continuum, and results in their having a very much higher hull speed than he ever envisioned from his observations in the order of 30+ knots is not unusual for these boats. Certainly the boats with this sort of performance are very lightly loaded racing craft, but even the more heavily laden cruising boats do not have much trouble breaking the 1.34 barrier. If these sorts of speeds can be achieved under sail, than it should be much easier under power. Towing tank tests of long, slim hulls with high prismatic coefficients (fine hulls with a fairly even spread of displacement from bow to stern), such as our displacement powerboats exhibit, have shown no catastrophic increase in wave drag at speed/length ratios above approximately 1.4 such as occurs with "normal" displacement hulls. These high prismatic hulls have a higher displacement hull speed than is "normal." This test data is further supported by the precisely measured performance tests of such boats as the Zenith-47 Antaeus, the Awesome 2000, the Mako-61, the Jaybee and the Icarus 46 in the full-sized ocean test tank. All these boats have prismatic coefficients greater than 0.66 and all easily exceed their theoretical hull speeds, while returning exceptional fuel economy.

So it would seem that all we have to do is to make power catamarans with long, slim hulls, and then we will have speed, economy and accommodation. The potential is there, but is it really that simple? The answer, of course, is "no" not quite! If we compare a sailing catamaran with a keelboat, we will see that the catamaran has one immediately obvious advantage. It is lighter because it is able to eliminate the lead keel upon which the keelboat depends on for its stability. In the case of the powerboat, there is no such advantage. The catamaran may, in fact, be heavier than the monohull because of its increased area. All is not lost, however, because while the skin area is increasing by the square, the interior volume is increasing by the cube! This possible increase in weight may be a problem with planing catamarans because of their limited planing surface, but it does not mean that our dream is impossible.

The displacement catamaran is not as susceptible to overloading as is the planing craft. The hull speed of the displacement boat is largely dependent on the L:B ratio of the hulls and this does not change very much with modest overloading. This does, however, bring up one of the limitations of the displacement boat. To work successfully, the L:B ratio of the hulls should be in excess of 10, and preferably higher. Consequently, if high displacements and length restrictions force short, fat hulls on the designer, then the displacement approach will not be successful. In this situation the only recourse is to lengthen the hull until the requisite L:B ratio is obtained, or to use a planing hull form. It will be apparent from this, that the displacement concept would seem to have little place in boats shorter than 10m (32'), unless they can be built light or a very modest performance is required. I have designed smaller displacement boats that achieve quite credible 15-knot cruising speeds from very small horsepower (43 HP per side) engines. But if performance on par with planing vessels is required, then the displacement boat must be able to have long, slim hulls, preferably without the planing boats’ low deadrise, submerged chine sections, as this increases the drag substantially, and even more if the chines break the surface. This, then, is the approach we have taken with a lot of our power catamaran designs: long, slim, easily driven round-bilge, minimum wetted surface hulls that give performance on a par with planing craft, but with considerably better sea-keeping capability and better fuel economy.

It is, of course, possible to question whether these boats really are displacement craft. Current theory says that for vessels of this length, to go this fast, they must be planing. In fact, if we accept the usual definition of planing vessel, namely: that it has a speed/length ratio of more than 2, then these boats are clearly planing. However, a boat is said to be planing when most of its mass is supported dynamically by the downward directed thrust of the water. A vessel that is planing will typically have a bow out trim and will have bodily risen out of the water. The waters are muddied a little by the fact that there is no sudden jump from displacement to planing. It is a continuum and somewhere in the speed/length ratio range from 1.5 to 2 the craft would be considered to be in a "semi-displacement" mode. We have now designed a large number of displacement power cats exemplifying the "long and slim" approach of powerboat design.

The Zenith-47 displaces 13 tons fully loaded, and motors at 20 knots maximum much more economically at 16 knots with only two 122 kw (160 HP) pushing hulls with a 24.5 knot hull speed. A monohulled displacement boat of this length would have a hull speed of about 8.5 knots. The smaller Nomad and Cortez powerboats also have a similar hull speed but are optimized more for economy with slower speeds with small engines. The Icarus-46 has a top speed of 25 knots from two 150 kw (200 HP) turbo-charged diesels. At the upper end of the scale is the Mako-61, an 18.6m (61') game fishing boat with a hull speed of 37.5 knots which would yield an easy 30 knots with around 500 HP per side. In the interest of economy, this boat is intended to cruise at 16 knots with a maximum of 20 knots using twin 150 kwThese performances are very much faster than those of the traditional displacement boats of comparable size and are on a par with that of a planing boat of similar displacement, but with lesser power requirement and subsequently greater economy. I believe the performance of these designs demonstrates the potential of the displacement power catamaran to be that very elusive and ephemeral animal; the best of all possible worlds: combining excellent accommodation, comfort, and economical performance with good old-fashioned seaworthiness. It seems to me that there is no reason why this old "long and slim" principle should not be applied to lightweight boats with less superstructure and even finer hulls, to produce 30 or even perhaps 40 knots of fuss-free performance from quite modest horsepower.

In fact, this belief has been partially tested with two offshore designs: the 17.5m (57') Red Diamond II, designed for a Japanese client, capable of a top speed of 33 knots (cruising at 24) from twin 320 kw (430 HP) Yanmar diesels; and the 20m (65') Awesome 2000, which has a top speed of 28 knots, and an open ocean cruising range of 3,000 miles at 15-knot speed. This craft has made the trip from Long Beach, California to Hawaii using only her internal tanks. Although these displacement cats may not be the fastest things around in flat water, they have demonstrated an ability to maintain much higher average speeds than most other craft regardless of sea conditions. In situations where the high-speed planing monohull is forced to drastically reduce its speed, the displacement catamaran is able to continue on with very little reduction in performance.

This

ability is

displayed day in and day out by the rapidly expanding commercial

catamaran ferry fleets whose operators recognized the economic

advantages of this concept early on. It has often been pointed out that

many people with displacement boats try to push them too fast and,

consequently, would be better off with a planing boat. For these people

there is now another alternative: displacement boats with the

performance of planing craft and the frugal thirst and smooth comfort

of the traditional displacement boat.

For More Information, email us at Info@PedigreeCats.Com

Pedigree Cats, Inc.

1835 Ocean Avenue

Raymond, WA 98577 | Fax (360) 942-2936

Copyright, 2000, Pedigree Cats, Inc.

This site is maintained by KC Computers (360) 942-2810